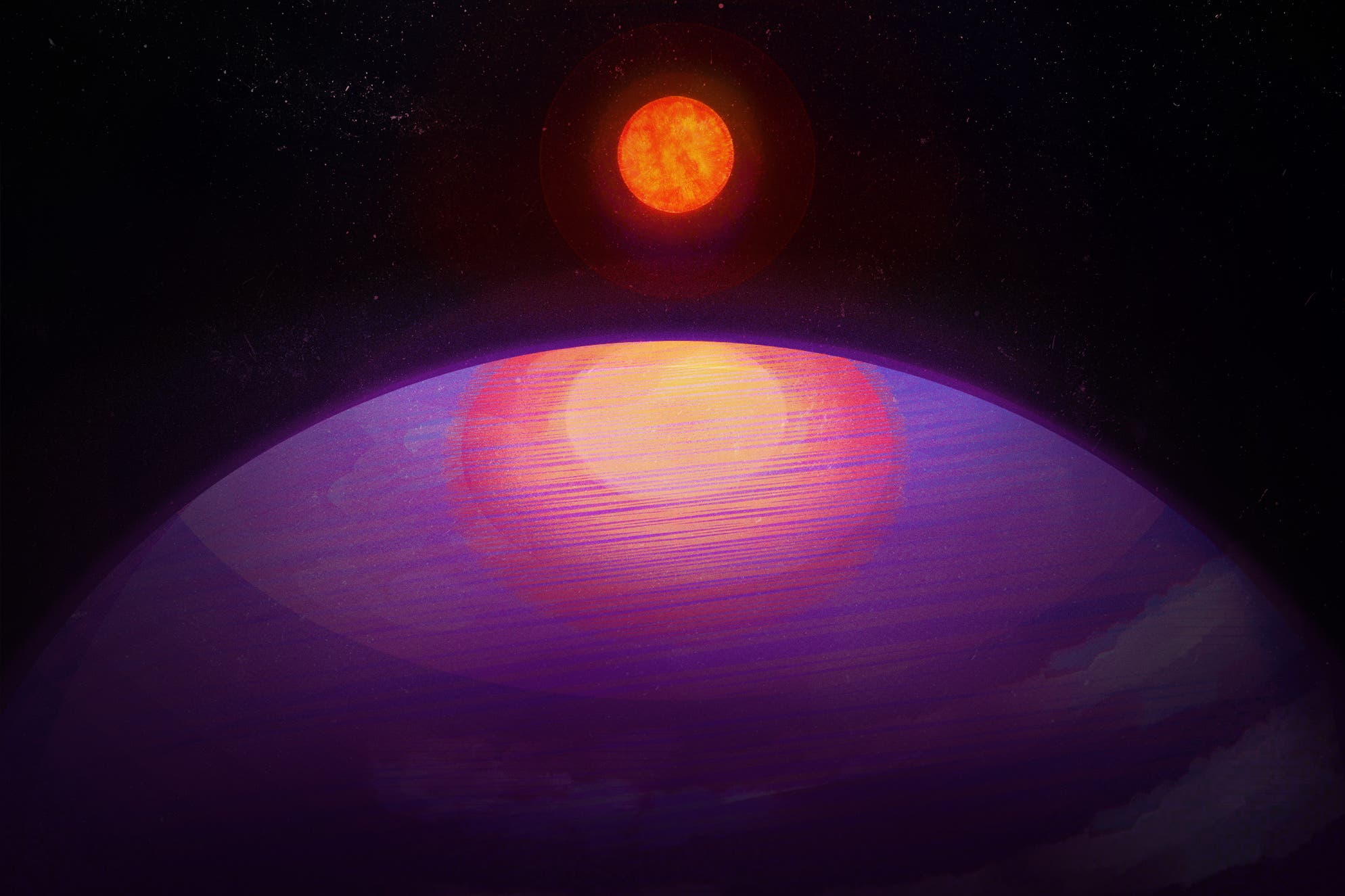

Planet too big for its sun ‘is challenging the idea of how solar systems form’

The team said this is the first time a planet with such a high mass has been spotted orbiting a low-mass star.

Astronomers have discovered a planet that is too big for its sun – challenging the understanding of how solar systems are formed.

The planet, named LHS 3154b, has a mass at least 13 times that of Earth and orbits the star LHS 3154, which is nine times smaller than the sun.

The team said this is the first time a planet with such a high mass – similar to that of Neptune – has been spotted orbiting a low-mass star.

The mass ratio of LHS 3154b and its host star is thought to be more than 100 times more than that of Earth and the sun.

We wouldn't expect a planet this heavy around such a low-mass star to exist

The researchers said the discovery, published in the journal Science, goes against the current understanding of how planets are formed around small stars.

Suvrath Mahadevan, a professor of astronomy and astrophysics at Penn State University in the US and co-author on the paper, said: “This discovery really drives home the point of just how little we know about the universe.

“We wouldn’t expect a planet this heavy around such a low-mass star to exist.”

When stars form, they draw large amounts of gas and dust that rotate around it in the form of a disc.

Some of this material can eventually go on to form planets.

However, Prof Mahadevan said the disc around LHS 3154 should not have enough solid mass to make such a large planet.

In theory, the amount of dust in the disc would need to be at least 10 times greater than what was observed to form LHS 3154b.

Prof Mahadevan added: “It’s out there, so now we need to re-examine our understanding of how planets and stars form.”

LHS 3154 is an ultracool dwarf star, which means it has relatively low temperatures compared with other stellar objects, such as the sun.

According to experts, this means planets capable of having liquid water on their surface will be much closer to their star in comparison to Earth and the sun.

Prof Mahadevan said: “Think about it like the star is a campfire.

“The more the fire cools down, the closer you’ll need to get to that fire to stay warm.

“The same is true for planets.

“If the star is colder, then a planet will need to be closer to that star if it is going to be warm enough to contain liquid water.”

The team used an instrument called the Habitable Zone Planet Finder (HPF), which is located at the Hobby-Eberly Telescope at the McDonald Observatory in Texas, to detect the planet.

HPF was designed and built by experts at Penn State University.

What we have discovered provides an extreme test case for all existing planet formation theories

Prof Mahadevan, who is principal investigator for the HPF project, said: “What we have discovered provides an extreme test case for all existing planet formation theories.

“This is exactly what we built HPF to do, to discover how the most common stars in our galaxy form planets – and to find those planets.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.